Furniture Of My Imagination

2021 – Project

(R) Researcher

Naomi Pullin

Assistant Professor in Early Modern British History, University of Warwick

What can pre-modern experiences of solitude tell us about what it means to be alone?

Solitude has long been perceived as problematic: beneficial only for a tiny minority of people. Its impact on our mental and physical health is a major area of concern. How to be alone and what constitutes ‘acceptable’ and ‘unacceptable’ states of aloneness is a widely debated topic in politics, the media and wider popular culture.

The aim of this research project is to explore how time spent alone was understood, described, and experienced in 17th and 18th century Britain. Drawing on a wide range of original sources, including personal diaries, letters and autobiographies, it considers the different ways in which solitude shaped the lives of pre-modern men and women.

At this time there was no vocabulary to describe the feeling of being ‘lonely’ or ‘alone’, which meant that solitude embodied a much broader range of meanings than it does today.

In adopting a more expansive understanding of what it means to be alone, the project explores both the benefits and struggles that many men and women encountered in their pursuit of solitude at different moments in their lives.

There is a very limited visual history of solitude before 1800, because the individual and their emotions were not central to artistic and literary works. Very few artists would have conceived of solitude as an embodied emotional state worthy of depiction. This collaboration therefore developed out of a desire to create a commissioned work that reflects the experiences of solitude as articulated by some of my pre-modern subjects.

About the collaboration

When the initial application was made to Coventry Creates, neither of us knew that we would be paired together or what the project would involve.

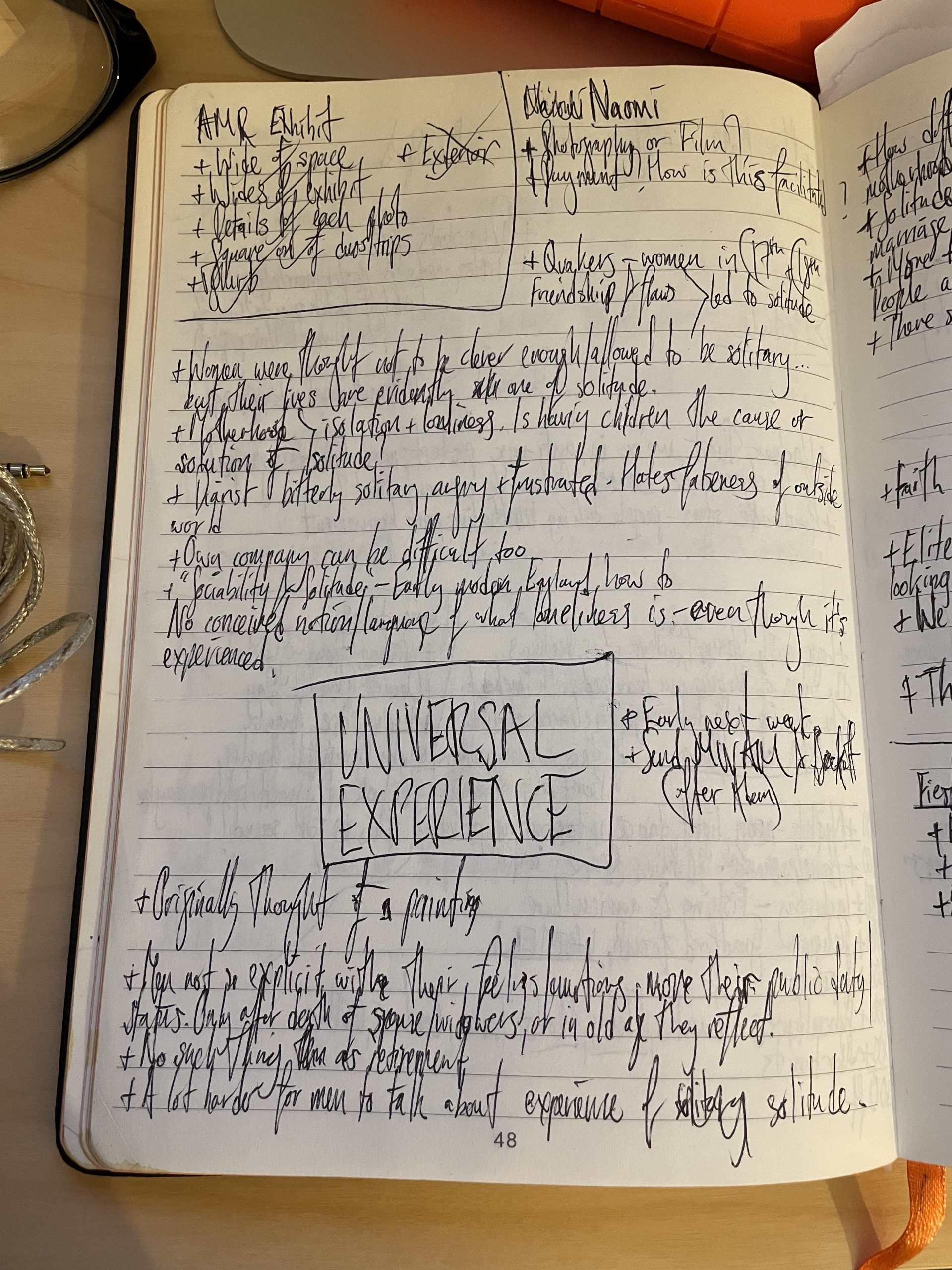

Our first meetings confirmed that we shared a very similar interest in capturing both the voluntary and involuntary aspects of solitude. We had a mutual interest in creating a social history of solitude that interrogated the benefits and struggles that men and women encountered in being alone in their everyday lives, whether in the 17th or 21st centuries. Particularly central to our questions was the gendered nature of solitude and whether it was acceptable for men to express and articulate the feelings they encountered when alone.

Our discussions on solitude deepened after Paul read some original excerpts from my research that depicted a range of feelings and representations of solitude. We both felt a strong connection to the writings of an eighteenth-century woman from Nottinghamshire called Gertrude Savile, who used her diary as a kind of cathartic document to overcome her feelings of deep isolation, whilst also talking candidly about her own personal failings and the faults of those that surrounded her.

One of the verses she penned called ‘Furniture for my Imagination’ conveyed powerfully the pleasures and perils that could accompany solitude.

She at once talks about her desire to cut herself off from the world, whilst also lamenting her wretched state, left with only her thoughts and pen and paper for company.

Paul was also finishing work on a film called ‘I, Dismantled’, which juxtaposed the empowering and destructive aspects of solitude. Its significance has been made all the more apparent with the loneliness that many people have experienced as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.

What we found

We were struck by the ways in which the writings of individuals like Gertrude Savile could encourage us to take comfort from solitude. Despite her desperately lonely situation, she was able to find peace and healing in the time she spent alone. It made us want to use this collaboration to challenge the modern notion that solitude always has to be a negative experience, which has too often been connected with loneliness. As Gertrude’s writings show, being alone could (and can be) something immensely empowering and nourishing.

The result

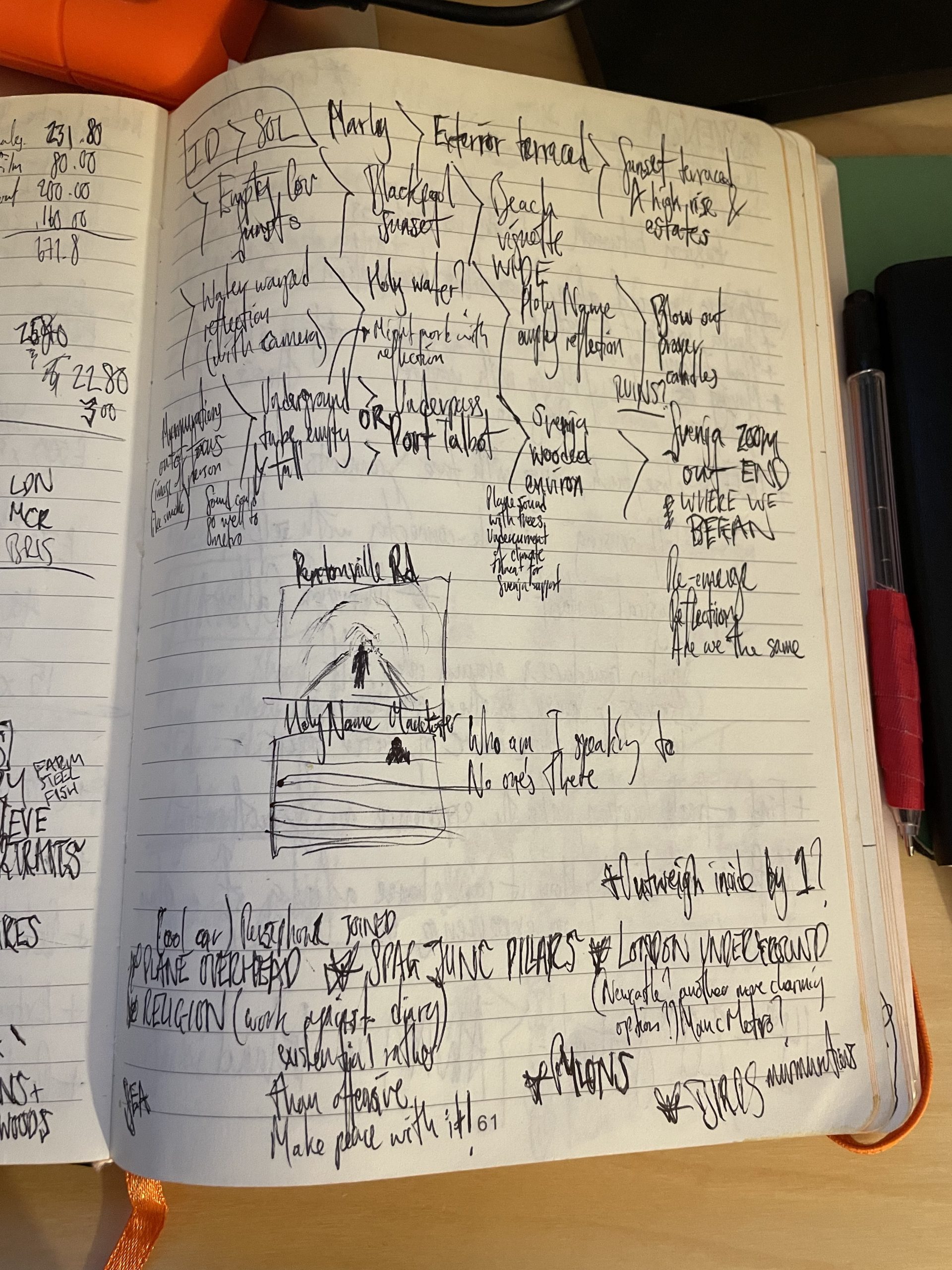

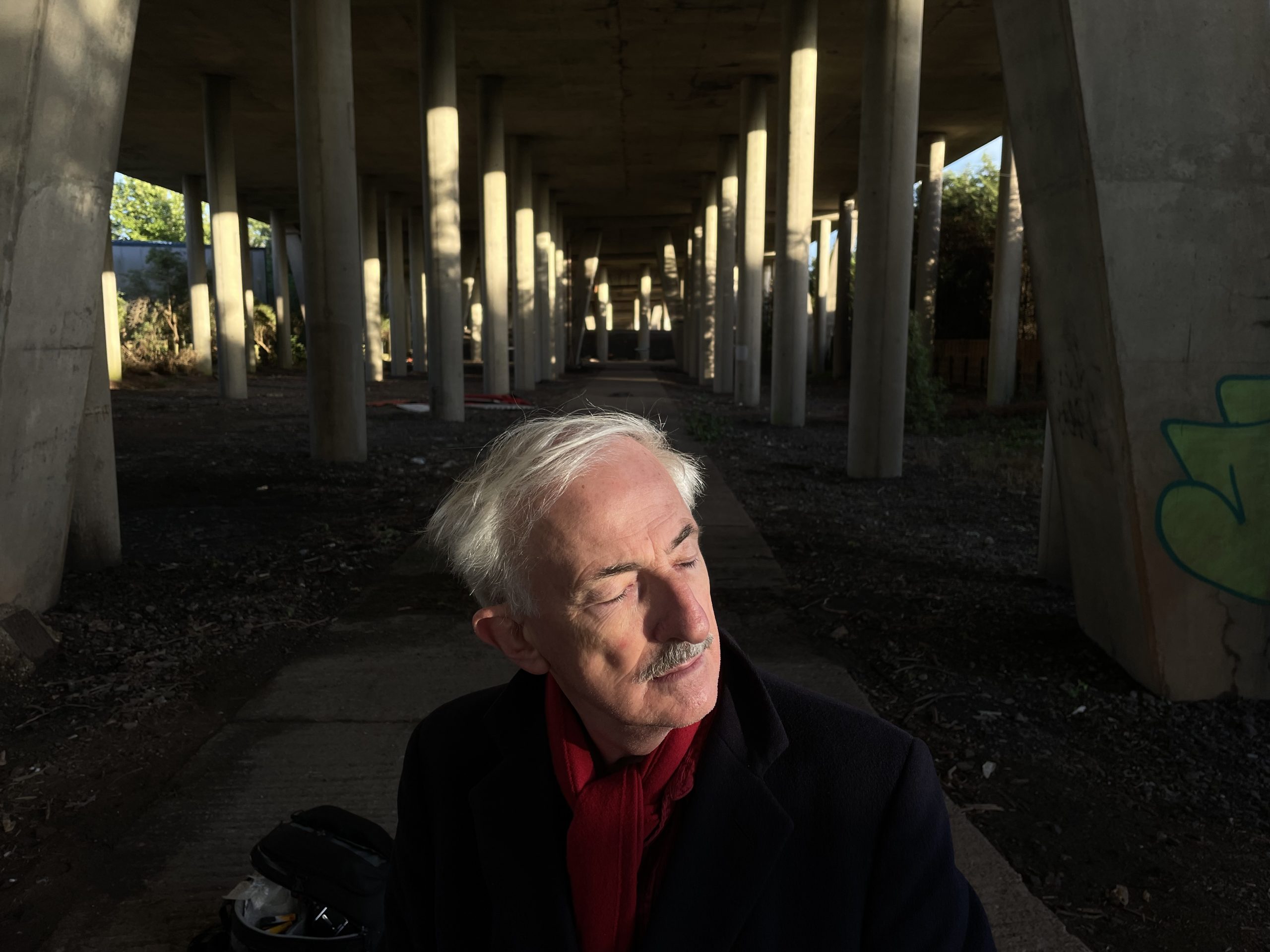

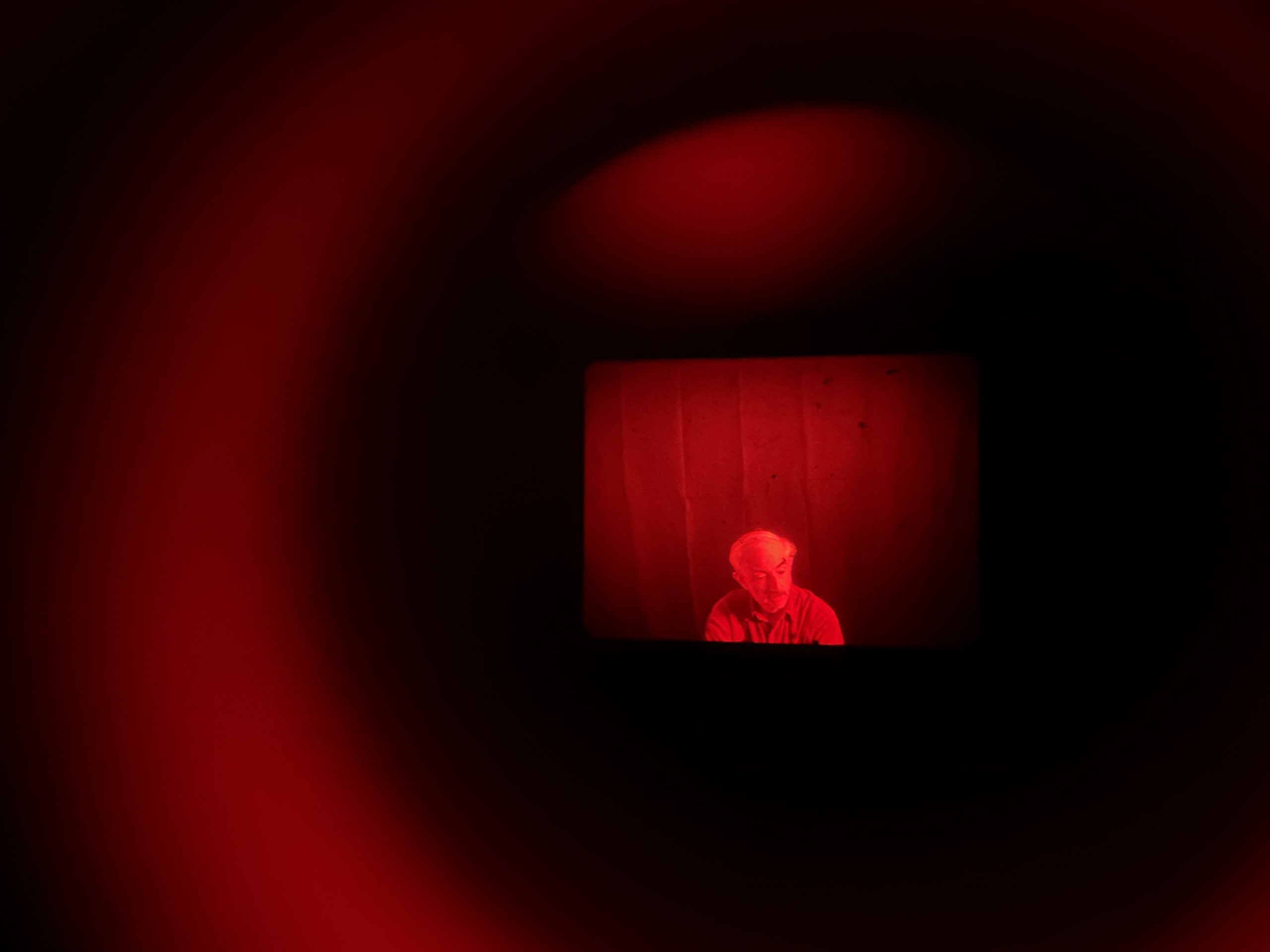

The final product, ‘Furniture of my Imagination’, is a 16mm film with accompanying portraits. Sharing a title with Gertrude’s verse on solitude, it captures the experience of being alone in different settings, spaces, and places in and around Coventry. Some spaces, like the church, graveyard, and rural landscape are timeless, connecting past and present. Other locations, like the field of pylons, train station, and motorway underpass remind us about the stark and, at times, alienating features of modern life. Whilst physically alone, the viewer is not completely confronted with an image of despair, and it is possible to read a sense of peace and contentment into the subject’s expressions and body language.

Whether sought or imposed, the solitude Paul has depicted is powerful. It captures the experience of being alone in a more nuanced way than other visual depictions, which tend to focus only on loneliness. And is made all the more richer by the poetic voiceover written by Paul in response to Gertrude’s thoughts on solitude.

I believe that the film reflects the richness of the discussions we have had around this topic. It has been a thought-provoking and useful experience for both of us.

The future

We hope to use this commission as a springboard for further collaboration into the experience of solitude (both past and present). We have a further event planned for the for the ‘Being Human’ strand of the Resonate Festival in January 2022, which will involve a screening of Paul’s work followed by wider discussion.

(A) Artist

Paul Daly

Filmmaker & Photographer

A study of solitude as a medicinal melancholy, a necessary and positive method for introspection and reflection as well as home to one’s own despairing and weighted thoughts of mortality. Focussing on my own father, the images were born from our relationship with this state of being. The city of Coventry’s culture, history and concrete landscape’s impact on my persona also plays its part.

The film was made in response to 18th Century diary excerpts provided by Warwick University based researcher Dr Naomi Pullin. The title was taken from a poem by diarist Gertrude Savile.